Humans are social creatures, but some things are just hard to talk about. For many people, mental health is one of those things.

But what if you can’t talk about something where the leading treatment is talk therapy? Maybe try speaking to someone who’s not human.

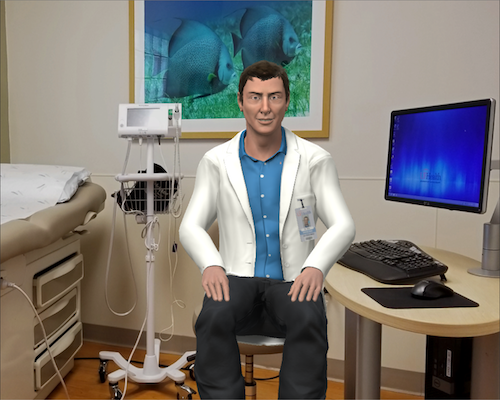

Benjamin Lok, a professor in the Department of Computer & Information Science & Engineering, has been studying applications of virtual humans for two decades. His research has led to the creation of dozens of virtual characters that appear in 1,500 different programs around the world and wrack up over a million virtual patient interactions a month with his company, Shadow Health.

Now, Lok has grants from the National Institute of Health and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention to employ and assess his virtual-human technology in the mental health domain.

Some of his characters will work with patients directly on a tablet application. His research has shown that by using human avatars, patients are more likely to relate to the characters and be more open than talking with a real doctor.

But patients aren’t the only ones who can benefit from the technology. How doctors, nurses and caretakers respond and communicate can largely affect the recovery process.

“We’re all each other’s keepers in some way,” Lok said. “All these different folks need assistance.”

Think about it this way. Just like pilots, nurses find themselves in high-stakes situations that require practice to make sure they’re handled appropriately — like talking to patients with suicidal ideation.

“Right now, how do you practice that?” Lok asked. “We’re doing the equivalent of just letting you get up in the airplane.”

What Lok and his team provide is a comfortable and safe environment where nurses can practice, make mistakes and learn to improve their conversation skills before interacting with real patients. Practicing with virtual patients helps nurses become more empathetic and medically accurate.

“Hopefully they remember to ask one more question — to listen and respond a certain way because they were able to get practice and get feedback,” Lok said. “My hope is that you and your family have gotten better care because people have used our technology to practice.”